Have you ever wondered how artisan bakers achieve such incredible depth of flavor and complex aroma in their breads, even sometimes when using commercial yeast? While long, slow fermentation and sourdough starters are well-known paths to flavor, there’s another powerful technique in the baker’s repertoire: using pre-ferments. You might see terms like poolish, biga, or pâte fermentée in more advanced recipes, sounding technical and perhaps a bit intimidating. But understanding and utilizing these methods can significantly elevate your bread, adding layers of flavor and improving texture without necessarily requiring the commitment of a sourdough starter.

So, what exactly are these mysterious pre-ferments, and why should an aspiring artisan baker bother with this extra step? Let’s demystify these common types and explore how incorporating them can unlock new dimensions in your yeast bread baking.

What is a Pre-ferment? (A Head Start for Flavor and Structure)

At its simplest, a pre-ferment is a portion of a bread recipe’s total ingredients – typically some of the flour, water, and a tiny amount of yeast (commercial or sometimes sourdough starter) – that is mixed together and allowed to ferment for a specific period before the final dough is mixed. This fermented mixture, brimming with yeast activity and flavorful byproducts, is then added as an ingredient to the main batch of dough.

Why Use a Pre-ferment? The Core Benefits:

The primary purpose of using a pre-ferment is to introduce the desirable characteristics of a long, mature fermentation into a dough that might otherwise have a shorter overall development time. It’s like giving your final dough a significant head start on flavor and structure. The key benefits include:

- Enhanced Flavor and Aroma: This is the most significant advantage. During the extended fermentation of the pre-ferment, yeast (and bacteria, if present) produce a wide array of complex organic acids, alcohols (like ethanol), esters, and other volatile compounds. These contribute significantly more depth, nuance, and a richer “wheaty” aroma compared to a simple “straight dough” mixed and fermented quickly.

- Improved Crumb Structure and Texture: Pre-ferments influence the final dough’s handling properties and crumb. Depending on the type used, they can increase dough extensibility (stretchiness, good for baguettes) or elasticity (strength, good for volume), potentially leading to a more open, tender, or satisfyingly chewy crumb.

- Better Keeping Quality: The organic acids produced during the pre-fermentation process act as natural preservatives, slightly lowering the dough’s pH. This can help the finished bread stay fresh and resist staling for a longer period compared to straight doughs.

- Potentially Reduced Final Proofing Time: Because the pre-ferment introduces a large, active population of yeast into the final dough, the bulk fermentation and/or final proofing time of the main dough may sometimes be slightly shorter.

Think of a pre-ferment as creating a concentrated dose of mature dough characteristics to boost your final loaf.

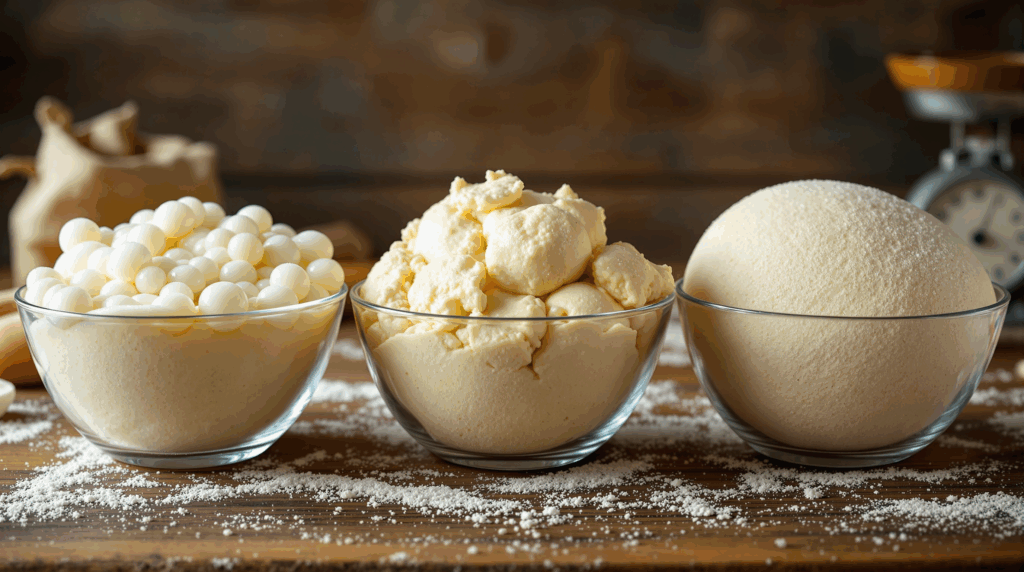

Poolish: The Wet & Wild One

Originating in Poland and later perfected by French bakers, poolish is a classic pre-ferment, especially associated with baguettes.

- Characteristics: A poolish is a very wet, liquid, sponge-like pre-ferment. It is typically made with:

- Equal weights of flour (often all-purpose or bread flour) and water, resulting in 100% hydration.

- A very tiny amount of commercial yeast (instant or active dry). The exact amount depends on the desired fermentation time and temperature (less yeast for longer/warmer ferments).

- Fermentation: Poolish is usually fermented at cool room temperature (around 65-72°F / 18-22°C) for a moderately long period, typically ranging from 8 to 16 hours. A mature, ready-to-use poolish will be very bubbly, fully risen, slightly domed on top or perhaps just beginning to recede slightly in the center. It should have a pleasant aroma – often described as nutty, alcoholic, and subtly tangy.

- Effects on Dough: Due to its high hydration and enzymatic activity, poolish primarily promotes extensibility (stretchiness) in the final dough. This makes it easier to shape long loaves like baguettes. It contributes to a creamy-colored, often irregular crumb structure, a thin and crisp crust, and adds complex, slightly tangy, and nutty flavor notes.

- Typical Use: Classic choice for baguettes, rustic French breads, ciabatta (sometimes), and even some pizza doughs. Recipes often call for the poolish to contain 20% to 50% of the total flour weight.

- Making a Basic Poolish (Example): If a recipe calls for a poolish using 150g flour: Combine 150g flour, 150g lukewarm water, and a scant pinch (e.g., 1/16 tsp or even less for very long ferments) of instant yeast in a container. Mix well until smooth. Cover and let ferment at cool room temperature for 12-16 hours (or as recipe specifies) until ripe.

Biga: The Stiff & Strong One

Hailing from Italy, biga offers different characteristics due to its lower hydration.

- Characteristics: A biga is a stiffer, dough-like pre-ferment. It typically contains:

- Flour (often a stronger bread flour).

- Water at a lower hydration level, usually 50% to 60% relative to the flour within the biga itself.

- A slightly larger amount of commercial yeast compared to a typical poolish (though still generally less than 1% of the biga’s flour weight).

- Fermentation: Similar to poolish, biga is often fermented for 12 to 18 hours at cool room temperature. Some variations might use shorter times at slightly warmer temperatures or with more yeast. A mature biga won’t look as obviously bubbly as poolish due to its stiffness but will have increased significantly in volume, feel puffy, and possess a distinctively strong, pungent, somewhat alcoholic or sharply tangy aroma.

- Effects on Dough: The lower hydration and different fermentation pathway (often producing more acetic acid relative to lactic acid compared to poolish) tend to promote strength and elasticity (the ability to spring back) rather than just extensibility in the final dough. This contributes to good loaf volume, a slightly chewier crumb compared to poolish, and a robust, tangy flavor profile. It generally has less enzymatic activity than poolish due to lower water content.

- Typical Use: Common in Italian breads like ciabatta (sometimes used in combination with poolish), pane francese, some types of pizza dough, and other breads where good structure and a chewy texture are desired. Like poolish, it often constitutes 20-50% of the total flour weight.

- Making a Basic Biga (Example): If a recipe needs a biga with 200g flour at 60% hydration: Combine 200g flour, 120g cool water, and a small amount (e.g., 1/8 tsp, depending on time/temp) of instant yeast. Mix briefly into a stiff, fairly dry, shaggy dough – it doesn’t need to be smooth or kneaded extensively. Cover tightly and let ferment at cool room temperature for 12-18 hours until puffy and aromatic.

Pâte Fermentée: The “Old Dough” Method

Literally translating from French as “fermented dough” or commonly called “old dough,” this method uses a piece of finished dough from a previous batch.

- Characteristics: Unlike poolish or biga which are mixed separately, pâte fermentée is simply a piece of fully developed bread dough (containing flour, water, salt, and yeast) that was made previously, having already undergone its bulk fermentation. Its hydration, salt content, and yeast percentage mirror the dough it was taken from.

- Fermentation: The reserved piece of dough continues to ferment slowly, especially if refrigerated overnight. This develops mature flavors and acidity.

- Effects on Dough: Adding this “old dough” to a new batch brings immediate mature dough characteristics: increased flavor complexity (from the acids and compounds developed during its own fermentation), improved dough strength (from its developed gluten), and a boost in yeast activity for the new dough. The effect is similar to adding a sourdough starter but relies on commercial yeast from the previous batch.

- Typical Use: A traditional technique in French baking to add depth to baguettes, croissants, pain de campagne, and other rustic loaves without requiring a separate pre-ferment mix. The amount used typically ranges from 10% to 30% of the new dough’s total weight.

- Making/Using: The most authentic way is to simply reserve a portion (e.g., 200-300g) of your regular bread dough after bulk fermentation but before final shaping. Lightly oil or flour it, store it in a covered container in the refrigerator for up to 2-3 days. Before mixing your next batch, let the reserved dough sit at room temperature for an hour or two to take the chill off, then cut or tear it into small pieces and incorporate it with the other ingredients during mixing. If you want to make pâte fermentée intentionally without a previous batch, you’d mix a small, complete dough (including salt) and let it ferment for several hours at room temperature or overnight in the fridge.

Choosing and Using Pre-ferments: Practical Tips

- Follow Recipe Guidance: When starting, use the type (poolish, biga, pâte fermentée) and percentage recommended in your specific recipe, as they are usually chosen for their distinct effects on that particular bread style.

- Maintain Cool Temperatures: For the long fermentation times typically involved (8-18 hours), ferment pre-ferments at a cool room temperature (around 65-72°F / 18-22°C is often ideal). Warmer temperatures will drastically shorten fermentation time and can lead to undesirable flavors or overly acidic results.

- Judge Ripeness Carefully: Learning to recognize when your pre-ferment is perfectly “ripe” is key. Use visual cues (volume, bubbles) and aroma. An under-ripe pre-ferment won’t contribute much flavor benefit. An over-ripe one (especially poolish or biga left too long) can become overly acidic or alcoholic, potentially weakening the gluten in the final dough or adding unpleasant flavors.

- Adjust Final Dough Ingredients: Remember that the flour, water, and yeast contained within your pre-ferment are part of the recipe’s total formula. You must subtract these amounts when calculating the ingredients needed for the final dough mix. Recipes using pre-ferments often call for slightly less yeast in the final dough mix as well.

- Incorporation: Liquid pre-ferments like poolish can usually be added along with the other liquids in the final dough mix. Stiffer pre-ferments like biga or pâte fermentée should be broken or cut into small pieces before adding to the mixer or bowl to ensure they incorporate evenly without requiring excessive mixing time.

- Experiment (Once Comfortable): After mastering basic usage, feel free to experiment. Try converting a favorite straight dough recipe to use a pre-ferment (calculating perhaps 30% of the flour into the pre-ferment). Play with fermentation times and temperatures for your pre-ferments to see how they influence the final flavor.

Conclusion: Unlocking Flavor with Forethought

Pre-ferments like poolish, biga, and pâte fermentée might sound like complex bakery jargon, but they represent powerful and accessible techniques for significantly enhancing the quality of your yeast breads at home. By simply mixing a portion of your ingredients ahead of time and allowing them to ferment, you unlock a deeper level of flavor complexity, improve dough structure, and extend the keeping quality of your loaves – achieving results often associated with sourdough or very long fermentation processes, but with the predictability of commercial yeast.

Don’t be intimidated by the French and Italian names. Understand the basic characteristics – poolish for wetness and extensibility, biga for stiffness and strength, pâte fermentée for using mature “old dough” – and follow recipe instructions carefully regarding ripeness and incorporation. Embracing pre-ferments is a fantastic way for any aspiring artisan baker to add another layer of control and creativity to their craft, pushing their bread from simply good to truly exceptional.